Fantasy football is a beloved game in America, with 40 million people participating every year. This national focus and the money poured into the game has triggered a surge in the development of advanced analytics, and in turn, an increasingly sharp field. Usage of once-niche metrics such as aDOT or YAC is proliferating even in casual home leagues and Vegas-beating projections are now widely available. In such an environment of democratized sophistication, edges are becoming increasingly difficult to find.

This paper explores a slim but potentially valuable edge that can be found in stacking. It’s a concept that’s fairly well understood by the fantasy football community but has, mistakenly in my opinion, been considered the near-sole domain of DFS fanatics. Although its uses in traditional fantasy formats are more limited, I would argue that it has its place.

And in a world in which even your dad is mapping out targets per route to win your family league, any edge is worth exploring.

Stacking, explained

Stacking strategies and an understanding of the underlying correlations have long driven DFS gameplay.

For the unfamiliar, the six or even seven-figure prizes you hear about on DraftKings and FanDuel are given to winners of tournaments with tens of thousands of entries. In order to come ahead of fields that large, lineups must hit their upsides (i.e. score a lot of points). By extension, the individual players within each lineup must all hit their upside outcomes at the same time. Consequently, managers will often “stack” their lineups with correlated players to ensure that there is an increased likelihood of simultaneous upside outcomes.

The classic manifestation of this is the quarterback-receiver stack. Tournament DFS players will almost always play a quarterback paired with one or more of his receivers, as their outcomes are understandably tied to each other’s.

To actualize this, below is Aaron Rodger’s fantasy output mapped against Davante Adam’s (all fantasy scoring in this paper follows DraftKings scoring). You’ll note that when Rodgers succeeds, so does Adams. By “stacking” the two and including both in the same lineup, you increase the likelihood that two players will hit their upside outcomes at the same time. This consequently increases the overall upside of that lineup.

Stacking in redraft leagues

Although stacking and correlations are generally understood by the fantasy community, their impact on traditional redraft strategy has been limited.

Thus far the most visible impact has been on macro drafting strategy. Advanced managers now understand that if a quarterback outperforms ADP, then his receivers are likely to as well. It is becoming an increasingly popular strategy to stack drafts in pursuit of this upside. Consider the following examples from 2021:

- By ADP (per Fantasy Football Calculator), Justin Herbert was drafted as the QB7 and finished as the QB2. Mike Williams was drafted as the WR48 and finished as the WR19.

- Tom Brady was drafted as the QB9 and finished as the QB3. Chris Godwin was drafted as the WR19 and finished as the WR10.

- Matt Stafford was drafted as the QB10 and finished as the QB5. Cooper Kupp was drafted as the WR16, below Robert Woods, and finished as the WR1 by an 80 point margin (PPR).

Managers who drafted any of the above pairs likely did very well for themselves in the 2021 season.

However, this is about the extent to which stacking concepts are applied to redraft leagues. Not many, if any, consider stacking or correlations when setting weekly lineups.

This is understandable. After all, DFS managers stack their lineups in a bid to achieve the upside necessary to come ahead of tens of thousands of competing lineups. In head-to-head redraft leagues, when you’re only competing against one other lineup in any given week, such pursuit of upside seems unnecessary. However, I would argue that there are many situations in which pursuit of upside, or at least an understanding of correlations, can be a significant edge.

An example

Consider a scenario in which your fantasy opponent has dominated the one o’clock games. All of his players played in the early slate and he’s built a daunting 50 point lead on you going into the late afternoon games. In your bid to close that gap, the only players you have left to play are Josh Allen (BUF) and one flex spot.

Your options for that flex spot are Darnell Mooney (CHI) and Cole Beasley (BUF). You check the premium fantasy rankings you’ve subscribed to and see that Mooney is a low end WR3 while Beasley is firmly a WR4. It seems you have no choice but to trust the rankings, submit your best possible lineup of Allen and Mooney, and hope for the best.

This is how the vast majority of redraft managers would approach this situation. I would, however, argue that this is a sub-optimal play.

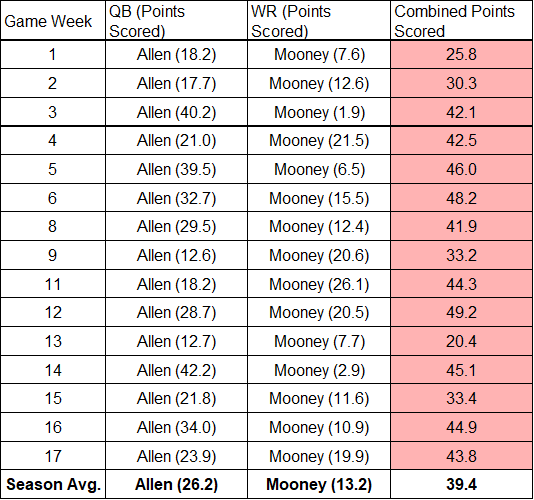

Let’s consider how pairing Allen with Mooney would have worked out in actuality. Below is a table of the combined points that an Allen–Mooney pairing would have produced in any given week in 2021:

We can see here that Mooney was a strong play on average, scoring an average 13.2 points a week. However, at no point did the pair of Allen and Mooney breach the 50 point threshold needed for victory. Put another way, this pairing would never have gotten you a win in the come-from-behind scenario in question.

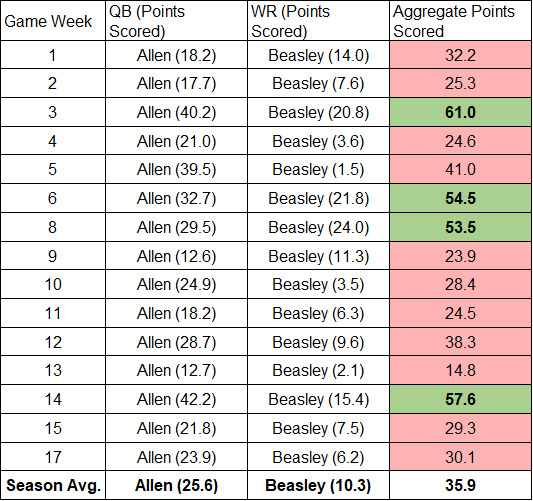

Now let’s repeat the exercise with Beasley:

We can see here that Beasley was actually a weaker play on average, scoring 10.3 points a week to Mooney’s 13.2. However, critically, the correlated pairing of Allen and Beasley combined for 50 points four times. Put another way, this pairing would have secured you a come-from-behind win 4 / 15 times, or 27% of the time.

This example is worth dwelling on. As I’ve noted, most fantasy managers would have chosen Mooney over Beasley in this scenario. Mooney, in most weeks, would have outscored Beasley, leading to the tempting conclusion that that was the right decision.

However, if the objective is to win your fantasy matchup rather than to score points, then the correct decision is to play a correlated, if otherwise inferior, Beasley. In a world in which fantasy managers still assume a direct link between fantasy points scored and winning matchups, understanding this can be a significant edge.

More scientifically

Now, as you may have guessed, the Mooney / Beasley scenario is a cherry-picked example I selected to make my point. What follows is a more blanket and scientific case to demonstrate that this strategy can be applied widely.

Let’s return to the come-from-behind scenario in which we must close a 50 point gap. If we break that down task into two distinct components, we can assume that we:

- need ~30+ points out of Josh Allen, and

- ~15-20+ points out of the flex spot.

Starting with #1, if we simplistically assume Allen’s last two years are predictive of the future, his odds of hitting upside outcomes are as follows:

From this, we can estimate that he has a 40% chance of producing the 30+ points necessary.

So far so good.

Next let’s see how likely we are to get 15-20+ points out of the flex spot.

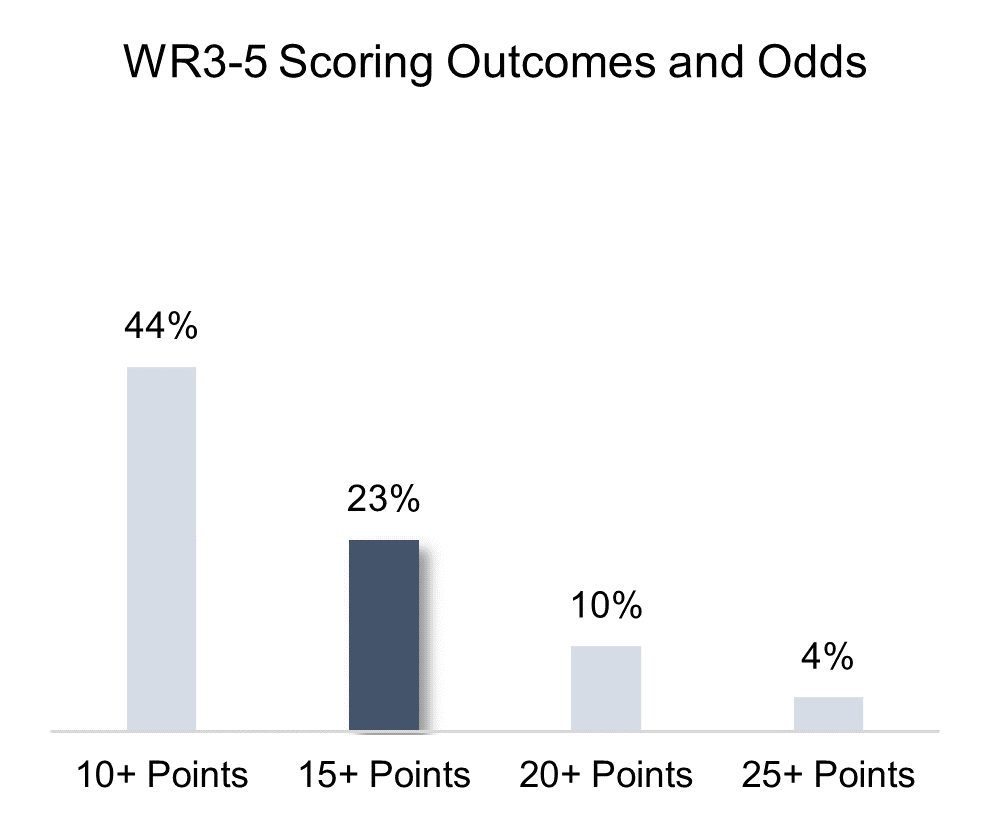

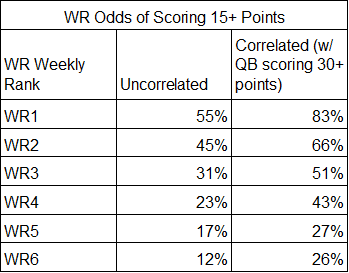

The chart below looks at historical WR3-5 scoring to infer odds of hitting upside outcomes. I use WR3-5s as this is likely the talent pool you’re pulling from to select your last flex players:

From this, we can estimate that the flex spot has a 23% chance of producing the 15+ points necessary.

If Josh Allen has a 40% chance at hitting his target upside, and the flex spot 23%, the odds that they combine for the necessary 50+ points is 9% (40% x 23%).

Not great.

However, the exercise thus far assumes we’re playing an uncorrelated flex player.

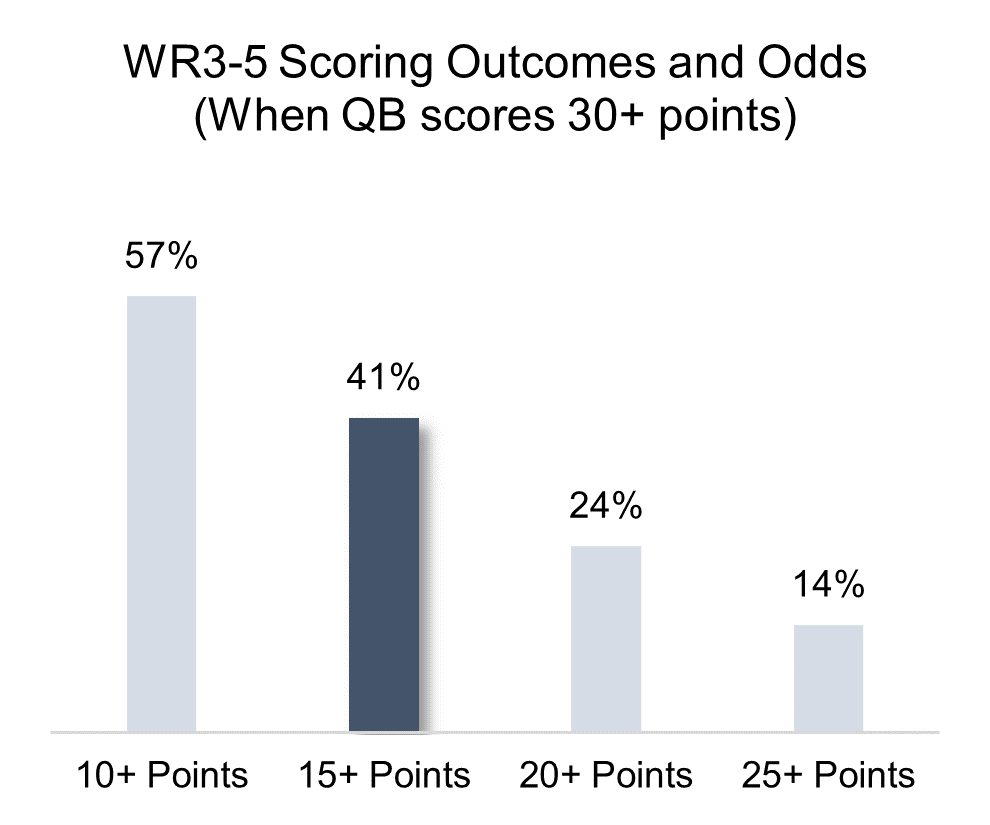

The next chart looks at historical WR3-5 performance, but this time, only at receivers whose quarterbacks scored 30+ points. We can interpret the results as indicative how one of Josh Allen’s receivers would perform if he too hit that 30 point mark. Unsurprisingly, the odds are much better:

The odds of a correlated receiver hitting 15+ points is now 41% (versus the 23% before). The combined odds for Allen and one of his receivers to hit 50+ points is therefore 16% (40% x 41%).

16% still may not feel like much, but it’s a monumental improvement. Proportionally, increasing your win probability from 9% to 16% represents a 78% increase in your equity. That’s a significant boost that speaks to the power of situational stacking.

Win probability, not points

We’ve now established that quarterback-receiver stacks have a higher probability of hitting upside outcomes than two otherwise equal but uncorrelated players.

You’ll recall that in the Beasley / Mooney scenario, I even made the case that a correlated WR4 could, situationally, be a better play than an uncorrelated WR3. Below is a table that supports that hypothesis over a larger sample size. An uncorrelated WR3 has a 31% chance of clearing 15 points. A WR4 paired with a quarterback that scores 30+ points has a 43% chance of doing so. In a come-from-behind situation when both your quarterback and receiver must hit their upsides, the correlated WR4 is the superior play:

This holds true across receiver tiers. A correlated WR2 offers more upside than an uncorrelated WR1. A correlated WR3 offers more upside than an uncorrelated WR2, so on, and so forth. I’ll call out that sample sizes are limited and that it’s possible that the benefit of stacking is not as clear cut as it appears above. However, it seems evident to me that if the situation demands, you should consider moving down a tier to opt for a correlated play.

At the risk of repetition, I’ll emphasize this point. Under the current mainstream thinking, almost no redraft manager is willing to, or even knows to, sacrifice projected points for hypothetical upside when necessary. Such managers will very often leave win probability on the table. Being one of the 1% of managers capable of occasionally squeezing out a few extra percentage points is a massive edge.

In practice

One question worth asking is how practical this insight is. The comeback scenario I’ve outlined, in which you’re down with a late afternoon quarterback and a few flex spots remaining, is a fairly specific one, one which doesn’t seem like it’d come around often. However, let’s do the math out.

If we assume that roughly a third of NFL games occur in the late afternoon or Sunday night slates, we can assume similar odds that your fantasy quarterback will play in that window. A fantasy regular season lasts 14 weeks. If you’re lucky and navigate your way through your playoffs, 17. One third of 17 weeks amounts to 5-6 weeks a year that you’re playing a late afternoon quarterback. For those of you in multiple leagues, that may add up to 15+ weeks, or instances, a year. Of those 15, it’s a fair bet that you’ll need a significant comeback in a few. One of those instances may be in the fantasy playoffs, or even a championship matchup.

It’s a scenario that will plausibly come up a few times each season. I would therefore argue that it’s one worth thinking through and being prepared for.

Execution

Execution of the strategies outlined in this paper can take a couple forms. The first is to preemptively draft and roster one of your quarterback’s low-end receivers to have available as a tactical option throughout the season.

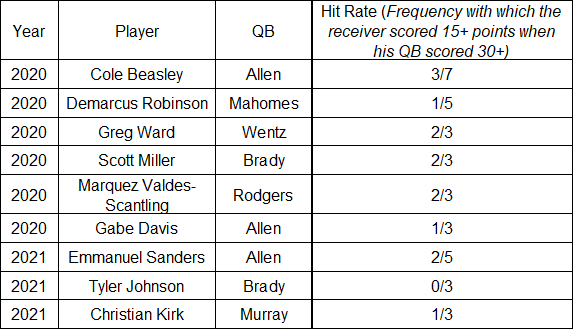

Let’s take a look at some of the players that popped up frequently in my analysis. These are WR4-6 type players with somewhat affordable ADPs:

There’s some value to be found here. John Brown in 2020 and Cole Beasley in 2021 would have served as situationally valuable and roster-worthy flex options for Josh Allen owners.

However, depending on your larger strategy, there may have been better fits for your team at this point in the draft. For Zero-RB adherents, these rounds are replete with value. Darrel Williams, Mark Ingram, and Devontae Booker all had 13th round ADPs in 2021 and went on to provide valuable starts for their owners.

However, further down the draft, I believe that the case for taking a stackable low-end receiver grows stronger. Below are some other players that I’d highlight that went in rounds 15+:

In the dying rounds of the draft, I’d argue that taking your quarterback’s WR3 or 4 is a much better use of draft capital than some fringe prospect you pulled off of a printed Matthew Berry article.

However, there will still be many times when there is simply too much value left in the draft to burn a pick on the MVS’s of the world. Fear not.

Note that some of the players listed above likely went undrafted in most leagues. My guess is that, Miller, Ward, and Johnson spent most of the seasons in question on waivers or free agency. Yet we can see that for Brady or Wentz (oofta) owners, there would have been many weeks in which picking up and starting one of them may have been a winning play. For participants in deep leagues with 3+ WR slots and 2+ flex, picking up a stackable receiver should always be a comeback consideration for that final flex spot.

Get creative

The best demonstration of the value of stacking in redraft fantasy is a come-from-behind scenario, in which I would advise consideration for a quarterback–receiver stack. However, there are a number of other ways to leverage the same concepts.

First, when attempting a comeback, also consider how your players correlate with your opponent’s lineup. All else held equal, you want to avoid positive correlation with your opponent. After all, if every time you benefit, your opponent does as well, catching up to them becomes very difficult.

Second, correlations go both ways. Positive correlation increases both your upside and downside. If you’re on the other side of the comeback attempt and are up big on your opponent, consider de-correlating your lineup to limit your downside, and therefore the probability that your opponent catches you.

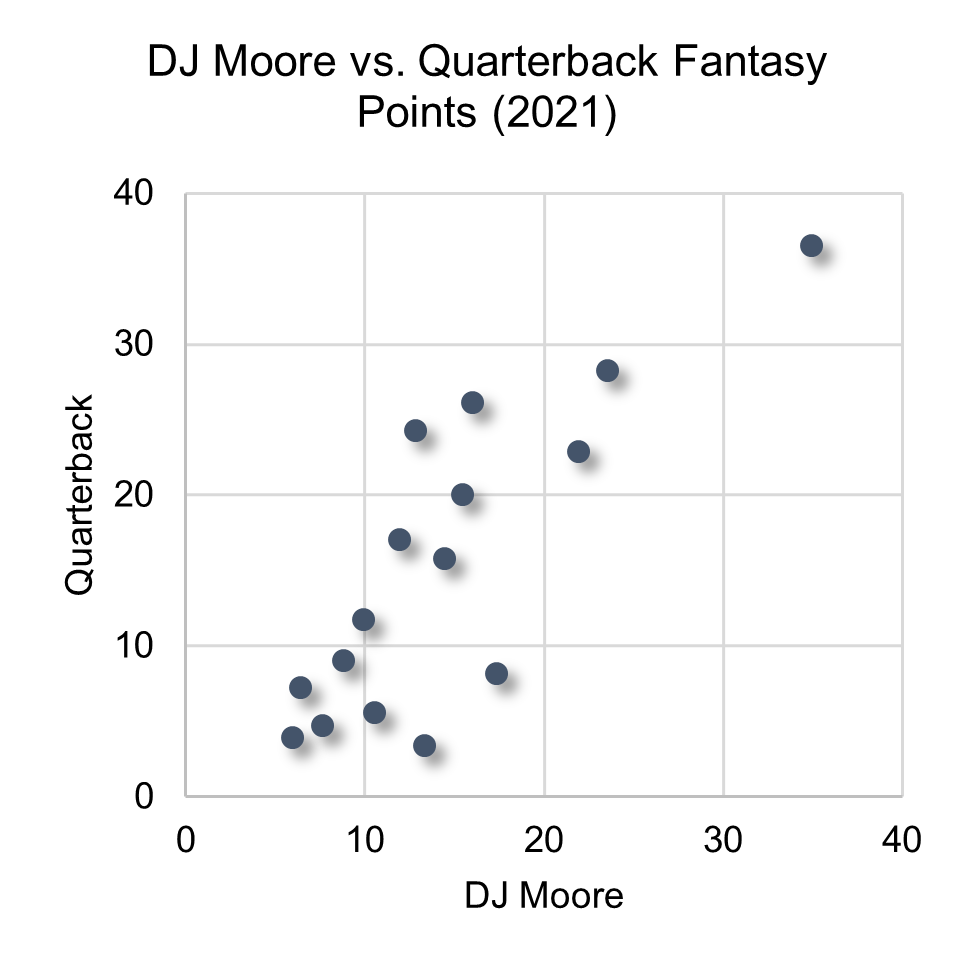

Third, get creative. I’ve drawn up the quarterback–receiver stacking strategy within a quarterback-to-receiver framework. There are scenarios in which you can go the other direction. Consider DJ Moore circa 2021 and how he correlated with his quarterback(s).

With Christian McCaffrey sidelined for much of the year, the Panthers offense largely ran through Moore. There was therefore almost a direct correlation between him and his quarterback’s output. There would have been tremendous value in picking Cam Newton up in the second half of the year and to start over the likes of Ryan Tannehill when in need of upside.

A caveat

Stacking is an incredibly potent weapon to add to your arsenal. It should not, however, be wielded blindly.

Consider a comeback scenario in which you have your quarterback and three or more flex players remaining. Compared to the Josh Allen scenario used throughout this paper, in which you only have one flex player, you have a multitude of ways you can achieve upside and stacking may not be necessary.

One way to theorize the math of this is to think of the players you have remaining as bets. Think about the Josh Allen scenario as one in which you have the following bets and are told you need to win $600:

Bet 1: $100 at +200 odds

Bet 2: $100 at +200

If you place those bets independently, there is no mathematical way to hit that $600 mark, even if both hit their +200 upside. If, however, you parlay those bets, you could walk away with an $800 win and clear that benchmark. As you may have guessed, this is akin to stacking.

Now consider how you might approach this decision if you have four bets to try to win $600:

Bet 1: $100 at +200 odds

Bet 2: $100 at +200

Bet 3: $100 at +200

Bet 4: $100 at +200

All of a sudden the calculus changes. All you need to do is hit on three out of the four independent bets to win the necessary $600 (I’m ignoring the fact, for this exercise, that losing the fourth bet in a Vegas setting would actually represent a $100 deduction from your winnings). I consider this akin to the thought process when you have multiple flex players left to try to stage a comeback.

Let’s do one more scenario. If you have those four bets but are suddenly told you need to win $900, you are once again in a position where placing those bets independently does you no good. You must, if you want to achieve a win, parlay, or stack at least one of them.

These examples highlight the situational considerations in making a stacking decision. The math will never be as clear cut as it is with the examples above. You will need to rely on some combination of back-of-the-envelope math and judgment. However, as a general rule in a comeback spot, the fewer players you have left remaining, or the larger the gap you need to make up, the more stacking should become a consideration.

In conclusion

Stacking as a strategy in redraft fantasy has yet to become widespread. For all my preaching on the topic, there is some reason for this. Unlike in DFS, it should a situational consideration rather than a golden rule.

However, we live in a world in which our opponents are getting ever sharper. Any edge we can find, even if marginal, is valuable. Moreover, the field is often reading the same fantasy articles we are, listening to the same podcasts, and scanning the same Twitter handles for injury updates. In this environment, differentiated thinking alone can serve to increase your odds.

Best of luck in the upcoming season. I hope this paper has served as useful food for thought!